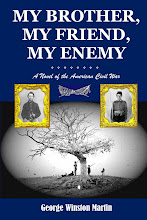

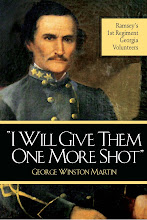

Just wanted to let everyone know that the release of I Will Give Them One More Shot has been delayed by a few weeks. The bindery where it is being processed evidently went down so the release has been pushed back until after the first of the year. Hopefully it will be out during the first week of January.

Once again - from the Martin family to yours - Merry Christmas to everyone, and to all a very Happy New Year! And to our troops serving overseas, along with their families waiting at home, we are grateful for your service, and wish you Godspeed.

George

Thursday, December 23, 2010

Monday, December 13, 2010

An Uneasy Christmas

Christmas – a season of jollity, delights, and feelings of goodwill toward one’s fellow man. For Christmas of 1860, however, the atmosphere over the United States was charged with antagonism, the air filled with gathering storm clouds which in a few short months would lead to war. Neither side had any idea of the ferocity of the whirlwind that was about to be unleashed.

The population of Georgia looked toward the holiday and the coming of the New Year with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. All eyes turned toward South Carolina, as delegates in Columbia debated the momentous issue of secession. On December 20, the Carolinians would sign their Ordinance of Secession, leading the way as the Southern states departed the United States.

In communities across the state, citizens from all walks of life, who in a few short months would be marching in the ranks of the First Georgia Volunteer Infantry, tried to maintain a semblance of normalcy in the face of the building tempest. James Newton Ramsey, who would become the colonel of the regiment, was practicing law along with his partner Albert R. Lamar, working out of an office over a bank in Columbus. James O. Clarke of Augusta, future lieutenant colonel, was listed in the 1860 census as a “master mason.” In Atlanta, George Harvey Thompson, son of prominent citizen and hotel owner Dr. Joseph Thompson, worked as a clerk. A graduate of the Georgia Military Academy and captain of the Gate City Guards, George Harvey would accept a captaincy in Governor Joseph E. Brown’s State Army prior to being elected as major of the First Georgia.

Newspapers were filled with editorials and letters from leading citizens railing against northern abolitionists and arguing for the necessity of separation from the Union. Even advertisements hinted at preparations for war. The Christmas day edition of the Columbus Enquirer contained an advertisement for J. W. Pease’s Bookstore, offering training manuals such as Scott’s, Hardee’s and McComb’s Tactics, a book on cavalry tactics, and another on bayonet exercises.

Christmas, 1860 – a time of joy – and of anxiety.

--------------------------------------

To each and all who have followed this blog from its beginning, and to all who come across it during their searches on the web, I wish you and yours a very Merry Christmas!

The population of Georgia looked toward the holiday and the coming of the New Year with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. All eyes turned toward South Carolina, as delegates in Columbia debated the momentous issue of secession. On December 20, the Carolinians would sign their Ordinance of Secession, leading the way as the Southern states departed the United States.

In communities across the state, citizens from all walks of life, who in a few short months would be marching in the ranks of the First Georgia Volunteer Infantry, tried to maintain a semblance of normalcy in the face of the building tempest. James Newton Ramsey, who would become the colonel of the regiment, was practicing law along with his partner Albert R. Lamar, working out of an office over a bank in Columbus. James O. Clarke of Augusta, future lieutenant colonel, was listed in the 1860 census as a “master mason.” In Atlanta, George Harvey Thompson, son of prominent citizen and hotel owner Dr. Joseph Thompson, worked as a clerk. A graduate of the Georgia Military Academy and captain of the Gate City Guards, George Harvey would accept a captaincy in Governor Joseph E. Brown’s State Army prior to being elected as major of the First Georgia.

Newspapers were filled with editorials and letters from leading citizens railing against northern abolitionists and arguing for the necessity of separation from the Union. Even advertisements hinted at preparations for war. The Christmas day edition of the Columbus Enquirer contained an advertisement for J. W. Pease’s Bookstore, offering training manuals such as Scott’s, Hardee’s and McComb’s Tactics, a book on cavalry tactics, and another on bayonet exercises.

Christmas, 1860 – a time of joy – and of anxiety.

--------------------------------------

To each and all who have followed this blog from its beginning, and to all who come across it during their searches on the web, I wish you and yours a very Merry Christmas!

Sunday, November 28, 2010

More Flags

The Walker Light Infantry, which would become Company “I” of the First Georgia, was constituted in early 1861 by combining two companies of so-called “minute men” in Augusta. The company was commanded by Captain Samuel H. Crump, and was issued “Mississippi” style rifles, .54 caliber. On March 23, 1861, the company received a new banner. The presentation was described in the Augusta Daily Constitutionalist the following day:

“The Walker Light Infantry, Capt. S. H. Crump, paraded yesterday afternoon. At four o’clock, the company marched to the City Hall, where a beautiful banner, “the work of fair hands,” was presented to them. JOHN B. WEEMS, of the Southern Republic, made the presentation, accompanying it with some patriotic and appropriate remarks.

Lieut. W. H. WHEELER, of the Walker Light Infantry, made the response in a very neat and totally appropriate little speech.

A detachment of the Washington Artillery fired a salute of seven guns on the river bank for the flag. The juvenile company, the Richmond Guards, who were on the balcony of the City Hall during the presentation, gave the banner three cheers.

The [field] of white ground, having the coat of arms of Georgia on one side, with the motto: “Dear our country; our liberty dearer.” On the other side is an uplifted arm grasping a sword. The flag is trimmed with a neat fringe, and is altogether creditable to the fair donors whose work it is; and they have entrusted it to worthy hands.

After the presentation, the company paraded for some time in Broad Street.”

The flag’s description is a little vague, not giving the precise layout of the state coat of arms and words. I’ve come up with a couple of variations to show what it may have looked like:

The obverse may have looked something like this:

“The Walker Light Infantry, Capt. S. H. Crump, paraded yesterday afternoon. At four o’clock, the company marched to the City Hall, where a beautiful banner, “the work of fair hands,” was presented to them. JOHN B. WEEMS, of the Southern Republic, made the presentation, accompanying it with some patriotic and appropriate remarks.

Lieut. W. H. WHEELER, of the Walker Light Infantry, made the response in a very neat and totally appropriate little speech.

A detachment of the Washington Artillery fired a salute of seven guns on the river bank for the flag. The juvenile company, the Richmond Guards, who were on the balcony of the City Hall during the presentation, gave the banner three cheers.

The [field] of white ground, having the coat of arms of Georgia on one side, with the motto: “Dear our country; our liberty dearer.” On the other side is an uplifted arm grasping a sword. The flag is trimmed with a neat fringe, and is altogether creditable to the fair donors whose work it is; and they have entrusted it to worthy hands.

After the presentation, the company paraded for some time in Broad Street.”

The flag’s description is a little vague, not giving the precise layout of the state coat of arms and words. I’ve come up with a couple of variations to show what it may have looked like:

The obverse may have looked something like this:

Thursday, November 25, 2010

Happy Thanksgiving

I would like to wish one and all a safe and Happy Thanksgiving! My best wishes go out to you and your families. And a special greeting to all of our men and women in uniform this holiday - thank you for your service.

George W. Martin

George W. Martin

Thursday, November 18, 2010

150 Years Ago

After Abraham Lincoln's election on November 6, 1860, communities across Georgia and the South intensified their recruiting efforts in anticipation of possible conflict. Existing militia units filled with volunteers, and new units popped up throughout the state.

Not every unit was having an easy time filling its ranks. In the town of Sandersville, members of the Washington Rifles were dismayed that their company was not yet at full strength. Deciding that a good scolding was in order, a committee drafted a letter to the populace, which appeared in the November 20 edition of the Sandersville Central Georgian:

To the People of Washington County:

The undersigned were appointed a committee to address you in behalf of the Washington Rifles. As the Rifles stand alone, it would be naturally supposed that out of a regiment which would muster more than a thousand efficient men, at least one in ten would lead them to sustain one volunteer corps. The result, however, does not justify this opinion; and the Washington Rifles as a Company, has the mortification of seeing in other counties large and flourishing volunteer companies—while old Washington can scarcely muster fifty men willing efficiently to serve the State.

While we would not impugn the patriotism of the old, or the gallantry and bravery of the young, need, hundreds would be found willing to serve, of what use in a time of war would be an undrilled militia? All experience has shown, that a course of military training is absolutely necessary to perfect the soldier, and although the universal use of fire arms—to which our youth from infancy are accustomed—makes them, individually, formidable, and perhaps invincible behind entrenchments. Yet in the open field, it is well known that the disciplined valor of a few, can accomplish more than that of four times their number of inexperienced recruits. To render efficient service to the country, then, the soldier must be trained—he must be drilled in the use of his weapons—trained to understand his duty, and how best to perform it. This is not the work of a day, though much may be accomplished in a short time. Usually, however, months of patient, daily training are found necessary to perfect the new recruit in company and regimental drill, without which he is unreliable in the field.

In view of the unsettled condition of our country, and of the gathering storm, which may burst in rain upon our heads, does not the voice of patriotism call upon all to prepare for the conflict—and shall Georgia call and Washington not answer? or shall our rights demand our service in the field, and we be unprepared for the conflict? Patriotism and honor alike forbid.

In behalf of our corps, we invoke the aid of our young countrymen—we invite you to join our ranks to aid us by your co-operation—to you your country looks for protection, to the youthful, the gallant, the brave! Will you be laggard? Will you shrink from the conflict? Will you prefer inglorious ease? Shall your country call in vain? Sons of Revolutionary sires, shall your country’s call be unheeded?

To another class of our fellow-citizens we address ourselves. To you who, having a large interest at stake at home, are disqualified for the field—we appeal to you to assist. There are young men who would enlist, but are unable to uniform themselves. It is your duty to assist them. Let each one of you uniform a young man of character, and the Washington Rifles will soon number a hundred or more efficient men, and be an honor to the county, whose name it bears, and whose interest it will ever be willing to protect and defend.

When we consider the means which are employed to disturb the peace of the South; when we see a religious fanaticism, even the most relentless, which would plunge our country into all the horrors of a servile war, deluging our peaceful land with blood, and resulting in the destruction of a race now peaceful, contented and happy, and upon whose labor the happiness of millions of the human race depend, self interest as well as patriotism demands that we be prepared to protect ourselves, and be prepared to meet and repel aggression at the threshold. Your fellow citizens,

J. R. SMITH

B. D. EVANS,

Committee.

Not every unit was having an easy time filling its ranks. In the town of Sandersville, members of the Washington Rifles were dismayed that their company was not yet at full strength. Deciding that a good scolding was in order, a committee drafted a letter to the populace, which appeared in the November 20 edition of the Sandersville Central Georgian:

To the People of Washington County:

The undersigned were appointed a committee to address you in behalf of the Washington Rifles. As the Rifles stand alone, it would be naturally supposed that out of a regiment which would muster more than a thousand efficient men, at least one in ten would lead them to sustain one volunteer corps. The result, however, does not justify this opinion; and the Washington Rifles as a Company, has the mortification of seeing in other counties large and flourishing volunteer companies—while old Washington can scarcely muster fifty men willing efficiently to serve the State.

While we would not impugn the patriotism of the old, or the gallantry and bravery of the young, need, hundreds would be found willing to serve, of what use in a time of war would be an undrilled militia? All experience has shown, that a course of military training is absolutely necessary to perfect the soldier, and although the universal use of fire arms—to which our youth from infancy are accustomed—makes them, individually, formidable, and perhaps invincible behind entrenchments. Yet in the open field, it is well known that the disciplined valor of a few, can accomplish more than that of four times their number of inexperienced recruits. To render efficient service to the country, then, the soldier must be trained—he must be drilled in the use of his weapons—trained to understand his duty, and how best to perform it. This is not the work of a day, though much may be accomplished in a short time. Usually, however, months of patient, daily training are found necessary to perfect the new recruit in company and regimental drill, without which he is unreliable in the field.

In view of the unsettled condition of our country, and of the gathering storm, which may burst in rain upon our heads, does not the voice of patriotism call upon all to prepare for the conflict—and shall Georgia call and Washington not answer? or shall our rights demand our service in the field, and we be unprepared for the conflict? Patriotism and honor alike forbid.

In behalf of our corps, we invoke the aid of our young countrymen—we invite you to join our ranks to aid us by your co-operation—to you your country looks for protection, to the youthful, the gallant, the brave! Will you be laggard? Will you shrink from the conflict? Will you prefer inglorious ease? Shall your country call in vain? Sons of Revolutionary sires, shall your country’s call be unheeded?

To another class of our fellow-citizens we address ourselves. To you who, having a large interest at stake at home, are disqualified for the field—we appeal to you to assist. There are young men who would enlist, but are unable to uniform themselves. It is your duty to assist them. Let each one of you uniform a young man of character, and the Washington Rifles will soon number a hundred or more efficient men, and be an honor to the county, whose name it bears, and whose interest it will ever be willing to protect and defend.

When we consider the means which are employed to disturb the peace of the South; when we see a religious fanaticism, even the most relentless, which would plunge our country into all the horrors of a servile war, deluging our peaceful land with blood, and resulting in the destruction of a race now peaceful, contented and happy, and upon whose labor the happiness of millions of the human race depend, self interest as well as patriotism demands that we be prepared to protect ourselves, and be prepared to meet and repel aggression at the threshold. Your fellow citizens,

J. R. SMITH

B. D. EVANS,

Committee.

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

A Face of the Civil War

A member of the First Georgia has been honored in Virginia. William S. Askew of the Newnan Guards, Company A of the First, appears on the new logo for the Manassas 150th Civil War Commemoration. The artist, Allan Guy of Allan Guy Design and Illustration of Manassas, Virginia, searched through the extensive holdings of the Library of Congress looking for just the right image of an early war soldier. When he came across Askew’s photograph, Guy knew he had the one he was looking for. Even though Askew did not serve at First or Second Manassas, Allan was taken by the “haunted” look in Askew’s eyes, and felt that Askew would represent well all the young, impressionable and eager young men who marched off to war in 1861. "I searched through a lot of images -- men and women -- with compelling faces, but this boy's eyes just shot out at you. This kid has the combination of age and eyes that are most direct," Allan explained in an interview. "A face like that is beyond comparison to even a period object or historic house. I wanted to make sure it had warmth because all too often history seems dead and gone."

Allan was also careful to use the appropriate First National flag in his illustration, instead of using the better known Southern Cross battleflag.*

The original image is displayed right. Askew strikes an suitably war-like pose as he holds his musket at attention, brandishing a brace of pistols in his belt. The private enlisted in the Newnan Guards on May 7, 1861, while the regiment was in Pensacola. During the retreat of the First and the Army of the Northwest from Laurel Hill in July, Askew was captured by Federal troops, but was able to escape and return to his regiment. In bad health as a result of his ordeal, Askew was discharged from the Newnan Guards on August 21. He later served in the 16th Georgia Cavalry Battalion, only to be captured again, and was imprisoned in Camp Morton, Indiana, until the end of the war.

I think Allan did a superb job with the logo.

-----------------------------------------

*Appropriate in that the Southern Cross did not exist until after the Battle of First Manassas (or Bull Run).

Allan was also careful to use the appropriate First National flag in his illustration, instead of using the better known Southern Cross battleflag.*

The original image is displayed right. Askew strikes an suitably war-like pose as he holds his musket at attention, brandishing a brace of pistols in his belt. The private enlisted in the Newnan Guards on May 7, 1861, while the regiment was in Pensacola. During the retreat of the First and the Army of the Northwest from Laurel Hill in July, Askew was captured by Federal troops, but was able to escape and return to his regiment. In bad health as a result of his ordeal, Askew was discharged from the Newnan Guards on August 21. He later served in the 16th Georgia Cavalry Battalion, only to be captured again, and was imprisoned in Camp Morton, Indiana, until the end of the war.

I think Allan did a superb job with the logo.

-----------------------------------------

*Appropriate in that the Southern Cross did not exist until after the Battle of First Manassas (or Bull Run).

Labels:

Newnan Guards,

Sesquicentennial,

Soldiers

Saturday, October 23, 2010

Georgia Sesquicentennial

The Tourism Division of the State of Georgia’s Department of Economic Development has just unveiled a new website dealing with Georgia’s commemoration of the state’s involvement in the Civil War. The website address is http://www.gacivilwar.org/. The stated purpose of the site is “to facilitate and promote an understanding of the Civil War and Georgia's role in it, as well as to promote heritage tourism that will inspire people to visit Georgia's Civil War historic sites and attractions. To serve as an online portal for communities and Civil War organizations in Georgia to promote their Civil War commemoration activities and events on one comprehensive site.”

On the site are tabs for War Between the States events and attractions, along with a timeline containing summaries of occurrences during each year of the war and an interactive map showing locations for battle sites, museums and other landmarks. There is a nice listing of links to Georgia Civil War-related sites. Definitely worth checking out.

Here is a list of other states’ Sesquicentennial sites:

Alabama: http://www.alabama.travel/activities/tours-trails/civil-war/civil-war/

Arkansas: http://www.arkansascivilwar150.com/

Connecticut: http://finalsite.ccsu.edu/page.cfm?p=2296

Indiana: http://www.in.gov/history/INCivilWar.htm

Kentucky: http://history.ky.gov/sub.php?pageid=132§ionid=5

Maine: http://www.maine.gov/civilwar/

Missouri: http://www.missouricivilwar.net/

New Jersey: http://www.njcivilwar150.org/index.asp

North Carolina: http://www.nccivilwar150.com/

Ohio: http://www.ohiocivilwar150.org/

Pennsylvania: http://www.pacivilwar150.com/

South Carolina: http://sc150civilwar.palmettohistory.org/

Tennessee: http://tnvacation.com/civil-war/

Virginia: http://www.virginiacivilwar.org/

West Virginia: http://www.pawv.org/civilwar150/index.htm

There is also a page on Facebook dedicated to the Sesquicentennial here.

On the site are tabs for War Between the States events and attractions, along with a timeline containing summaries of occurrences during each year of the war and an interactive map showing locations for battle sites, museums and other landmarks. There is a nice listing of links to Georgia Civil War-related sites. Definitely worth checking out.

Here is a list of other states’ Sesquicentennial sites:

Alabama: http://www.alabama.travel/activities/tours-trails/civil-war/civil-war/

Arkansas: http://www.arkansascivilwar150.com/

Connecticut: http://finalsite.ccsu.edu/page.cfm?p=2296

Indiana: http://www.in.gov/history/INCivilWar.htm

Kentucky: http://history.ky.gov/sub.php?pageid=132§ionid=5

Maine: http://www.maine.gov/civilwar/

Missouri: http://www.missouricivilwar.net/

New Jersey: http://www.njcivilwar150.org/index.asp

North Carolina: http://www.nccivilwar150.com/

Ohio: http://www.ohiocivilwar150.org/

Pennsylvania: http://www.pacivilwar150.com/

South Carolina: http://sc150civilwar.palmettohistory.org/

Tennessee: http://tnvacation.com/civil-war/

Virginia: http://www.virginiacivilwar.org/

West Virginia: http://www.pawv.org/civilwar150/index.htm

There is also a page on Facebook dedicated to the Sesquicentennial here.

Sunday, October 17, 2010

Sesquicentennial

With copyedit work for I Will Give Them One More Shot fairly well behind me, I’ve been taking the opportunity to re-read some of the books in my Civil War library. I just finished Reminiscences of the Civil War by General John B. Gordon of Georgia, and the final paragraphs got me to thinking about the upcoming Sesquicentennial.

Gordon’s book was published in 1903. In it, he makes no bones about his unabashed love and admiration for General Robert E. Lee. While he exhibits no great respect for several officers (in particular General Philip Sheridan), Gordon praises General Ulysses S. Grant for his magnanimity when at Appomattox he allows the officers to retain their side-arms and the soldiers to keep their horses. One would think that Gordon, who was wounded several times during the war and rose from a company captain to become one of Lee’s corps commanders, would be as entitled as any in the South to be bitter over its defeat. Instead, Gordon went on to serve his state and united country, becoming governor of Georgia and serving in the United States Senate.

In his book’s last paragraph, Gordon wrote what could be a guiding principle in Sesquicentennial observances:

Scarcely less prominent in American annals than the record of these two lives [Lee and Grant], should stand a catalogue of the thrilling incidents which illustrate the nobler phase of soldier life so inadequately described in these reminiscences. The unseemly things which occurred in the great conflict between the States should be forgotten, or at least forgiven, and no longer permitted to disturb complete harmony between North and South. American youth in all sections should be taught to hold in perpetual remembrance all that was great and good on both sides; to comprehend the inherited convictions for which saintly women suffered and patriotic men died; to recognize the unparalleled carnage as proof of unrivalled courage; to appreciate the singular absence of personal animosity and the frequent manifestation between those brave antagonists of a good-fellowship such as had never before been witnessed between hostile armies. It will be a glorious day for our country when all the children within its borders shall learn that the four years of fratricidal war between the North and the South was waged by neither with criminal or unworthy intent, but by both to protect what they conceived to be threatened rights and imperiled liberty; that the issues which divided the sections were born when the Republic was born, and were forever buried in an ocean of fraternal blood. We shall then see that, under God’s providence, every sheet of flame from the blazing rifles of the contending armies, every whizzing shell that tore through the forests at Shiloh and Chancellorsville, every cannon-shot that shook Chickamauga’s hills or thundered around the heights of Gettysburg, and all the blood and the tears that were shed are yet to become contributions for the upbuilding of American manhood and for the future defence of American freedom. The Christian Church received its baptism of Pentecostal power as it emerged from the shadows of Calvary, and went forth to its world-wide work with greater unity and a diviner purpose. So the Republic, rising from its baptism of blood with a national life more robust, a national union more complete, and a national influence ever widening, shall go forever forward in its benign mission to humanity.

Amen.

Gordon’s book was published in 1903. In it, he makes no bones about his unabashed love and admiration for General Robert E. Lee. While he exhibits no great respect for several officers (in particular General Philip Sheridan), Gordon praises General Ulysses S. Grant for his magnanimity when at Appomattox he allows the officers to retain their side-arms and the soldiers to keep their horses. One would think that Gordon, who was wounded several times during the war and rose from a company captain to become one of Lee’s corps commanders, would be as entitled as any in the South to be bitter over its defeat. Instead, Gordon went on to serve his state and united country, becoming governor of Georgia and serving in the United States Senate.

In his book’s last paragraph, Gordon wrote what could be a guiding principle in Sesquicentennial observances:

Scarcely less prominent in American annals than the record of these two lives [Lee and Grant], should stand a catalogue of the thrilling incidents which illustrate the nobler phase of soldier life so inadequately described in these reminiscences. The unseemly things which occurred in the great conflict between the States should be forgotten, or at least forgiven, and no longer permitted to disturb complete harmony between North and South. American youth in all sections should be taught to hold in perpetual remembrance all that was great and good on both sides; to comprehend the inherited convictions for which saintly women suffered and patriotic men died; to recognize the unparalleled carnage as proof of unrivalled courage; to appreciate the singular absence of personal animosity and the frequent manifestation between those brave antagonists of a good-fellowship such as had never before been witnessed between hostile armies. It will be a glorious day for our country when all the children within its borders shall learn that the four years of fratricidal war between the North and the South was waged by neither with criminal or unworthy intent, but by both to protect what they conceived to be threatened rights and imperiled liberty; that the issues which divided the sections were born when the Republic was born, and were forever buried in an ocean of fraternal blood. We shall then see that, under God’s providence, every sheet of flame from the blazing rifles of the contending armies, every whizzing shell that tore through the forests at Shiloh and Chancellorsville, every cannon-shot that shook Chickamauga’s hills or thundered around the heights of Gettysburg, and all the blood and the tears that were shed are yet to become contributions for the upbuilding of American manhood and for the future defence of American freedom. The Christian Church received its baptism of Pentecostal power as it emerged from the shadows of Calvary, and went forth to its world-wide work with greater unity and a diviner purpose. So the Republic, rising from its baptism of blood with a national life more robust, a national union more complete, and a national influence ever widening, shall go forever forward in its benign mission to humanity.

Amen.

Saturday, October 2, 2010

Flag of the Southern Guard

On Tuesday, February 5, 1861, an overflow crowd jammed into Temperance Hall in Columbus, Georgia, eager to witness a special ceremony. That evening Company “D” of Columbus’s Southern Guard was presented with a brand-new flag, sewn by Mrs. W. J. McAlister and other ladies in her family. The banner was described in an article in the Columbus Weekly Times:

“It was made of rich white silk doubled, and elaborately executed in the handsomest manner. The arms of the Republic of Georgia was painted on one side, beneath the arch of which were the words in gold: “Cotton is King.”

The sentinel usually seen on the Georgia Coat of Arms was moved to the left side, and in his place was positioned a slave seated on a bale of cotton. The article continued:

Above the arch was the Latin quotation, “Non nobis solum sed patrie et amicie”—“Not for ourselves alone, but country and friends.” On the reverse in a semi-circle form were the words “Southern Guard” in gilt letters, with a large “D” beneath; the whole surrounded by wreaths of acorns, and the cotton plant with its bolls in all stages of growth—The banner was trimmed with rich fringe about three inches deep.”

The banner was received on behalf of the company by Lieutenant James N. Ramsey. Three months later, the Southern Guard became Company B of the First Georgia Volunteer Infantry, and Ramsey was elected as the regiment’s colonel.

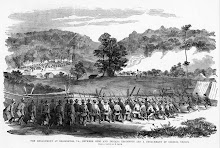

During the Army of the Northwest’s retreat from Laurel Hill on July 13, 1861, several company flags were stowed in wagons as the army struggled to escape their Union pursuers in the pouring rain and bottomless mud. As the wagons slowly made their way along a narrow trace along the side of Pheasant Mountain, several slid off the side, crashing down into the ravine below. The wagon carrying the Southern Guards’ flag was one meeting this fate. Federal troops picking through the wreckage came across the banner, along with that of the Gate City Guards. Further along, the standard of the Washington Rifles was found in a wagon abandoned at a river crossing below Kalers Ford. It is uncertain exactly where the flags were conveyed from there, but the Southern Guard’s banner was eventually displayed with a collection of other captured banner. The illustration above is from the March 15, 1862 edition of the New York Illustrated News, which described this collection of Rebel flags.

Sadly, though many of the flags captured in Northwestern Virginia were returned to Georgia (the banner of the Gate City Guards is held by the Atlanta History Center, and the Washington Rifles flag is in the collection of the Georgia Capitol Museum in Atlanta), no trace of the Southern Guard’s standard has survived. Using the newspaper and other descriptions, along with the above illustration, I have created what I believe is a close approximation of the banner:

And the obverse:

Maybe someday this beautiful flag will be discovered and restored to the state of Georgia.

(Thanks to Greg Biggs for the image from the New York Illustrated News)

“It was made of rich white silk doubled, and elaborately executed in the handsomest manner. The arms of the Republic of Georgia was painted on one side, beneath the arch of which were the words in gold: “Cotton is King.”

The sentinel usually seen on the Georgia Coat of Arms was moved to the left side, and in his place was positioned a slave seated on a bale of cotton. The article continued:

Above the arch was the Latin quotation, “Non nobis solum sed patrie et amicie”—“Not for ourselves alone, but country and friends.” On the reverse in a semi-circle form were the words “Southern Guard” in gilt letters, with a large “D” beneath; the whole surrounded by wreaths of acorns, and the cotton plant with its bolls in all stages of growth—The banner was trimmed with rich fringe about three inches deep.”

The banner was received on behalf of the company by Lieutenant James N. Ramsey. Three months later, the Southern Guard became Company B of the First Georgia Volunteer Infantry, and Ramsey was elected as the regiment’s colonel.

During the Army of the Northwest’s retreat from Laurel Hill on July 13, 1861, several company flags were stowed in wagons as the army struggled to escape their Union pursuers in the pouring rain and bottomless mud. As the wagons slowly made their way along a narrow trace along the side of Pheasant Mountain, several slid off the side, crashing down into the ravine below. The wagon carrying the Southern Guards’ flag was one meeting this fate. Federal troops picking through the wreckage came across the banner, along with that of the Gate City Guards. Further along, the standard of the Washington Rifles was found in a wagon abandoned at a river crossing below Kalers Ford. It is uncertain exactly where the flags were conveyed from there, but the Southern Guard’s banner was eventually displayed with a collection of other captured banner. The illustration above is from the March 15, 1862 edition of the New York Illustrated News, which described this collection of Rebel flags.

Sadly, though many of the flags captured in Northwestern Virginia were returned to Georgia (the banner of the Gate City Guards is held by the Atlanta History Center, and the Washington Rifles flag is in the collection of the Georgia Capitol Museum in Atlanta), no trace of the Southern Guard’s standard has survived. Using the newspaper and other descriptions, along with the above illustration, I have created what I believe is a close approximation of the banner:

And the obverse:

Maybe someday this beautiful flag will be discovered and restored to the state of Georgia.

(Thanks to Greg Biggs for the image from the New York Illustrated News)

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

William Wing Loring

Once the disaster of Garnett’s defeats in Western Virginia became known, Richmond dispatched a new commander to take charge of the demoralized Army of the Northwest. When Brigadier General William Wing Loring arrived in Staunton, he was stunned to find soldiers from the First Georgia Regiment scattered across the countryside. Livid at what he considered a serious breach of discipline, Loring promptly had Colonel Ramsey placed under arrest.

William Wing Loring was born in Wilmington, North Carolina, on December 4, 1818. At the age of four his parents moved to St. Augustine, Florida. Loring began his military career at the tender age of fourteen, joining the Florida militia to fight against the Seminole Indians, eventually achieving the rank of second lieutenant. Sent by his parents to Virginia to complete his education, Loring graduated from Georgetown University in 1840. Returning to Florida, he practiced law and was elected to the Florida legislature.

In 1846, Loring was appointed as captain in the Regiment of Mounted Rifles, and was quickly promoted to major. The Regiment saw action during the Mexican War. While leading a charge at Chapultepec, Loring was hit in his left arm, and the shattered limb was amputated. For his meritorious service, Loring was brevetted to Lt. Colonel and Colonel. After the war, Loring was posted to the Oregon territory, and later served at various western outposts.

In late 1856 he was promoted to colonel, giving him the distinction of being the youngest full colonel in field command in the U.S. Army. Loring took a leave of absence in 1859 to tour Europe and the Middle East. Upon his return to the United States, he was given command of the Department of New Mexico.

With the secession of Florida, Loring sided with the Southern cause, resigning his commission in May of 1861. Traveling to Richmond, he was given a commission as brigadier general. Following the death of General Robert S. Garnett, Loring was ordered to take command of the Army of the Northwest. Loring was less than enthusiastic when shortly thereafter General Robert E. Lee arrived to take charge, as Loring had ranked Lee in the old army, and still considered him a subordinate. When in December 1861, Loring and three of his brigades were attached to the forces of General Thomas J. Jackson at Winchester, Loring found himself constantly at odds with the secretive “Stonewall.” The simmering feud finally led to Jackson preferring charges against Loring. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin decided it was time to separate the warring generals. The Army of the Northwest was broken up, and Loring was promoted to major general and given command of the Department of Norfolk, then later the Department of Southwestern Virginia. In January of 1863 he was ordered to the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana, where he commanded a division in the army of General Joseph Pemberton. In an engagement against Union gunboats, Loring shouted to his men to “give them blizzards!” He was known as “Old Blizzards” from then on. During the Vicksburg Campaign, his division was cut off from Pemberton’s force at Champion Hill. Loring marched his troops to join forces with General Joseph E. Johnston’s, where his division was attached to the corps of General Leonidas Polk. During the Atlanta Campaign, Loring was wounded at the Battle of Ezra Church. Loring remained with the Army of Tennessee through Hood’s Tennessee and Johnston’s Carolinas Campaigns, surrendering with that army at Durham Station, North Carolina, on April 26, 1865.

Following the end of the war, Loring tried his hand at banking in New York City, then in December 1869, he accepted a commission in the Egyptian Army. He spent ten years in Egypt, ultimately earning the rank of “Fareek Pasha” (major-general). Returning to the Florida, Loring ran unsuccessfully for U.S. senator, after which he moved back to New York City. He died there on December 30, 1886, and his remains were returned to St. Augustine, Florida, and interred in Woodlawn Cemetery.

Friday, September 10, 2010

Colebrook Historical Society

Have just returned from my trip to New England, where I had the pleasure of speaking to the Colebrook Historical Society of Colebrook, New Hampshire about the two Marshall brothers who served on opposite sides during the Civil War. The evening went very well, and I would like to thank the members of the Society for their enthusiastic reception.

Thursday, September 2, 2010

Henry Rootes Jackson

Henry Rootes Jackson was born June 24, 1820, in Athens, Georgia, son of a prominent professor at the University of Georgia. Jackson graduated from Yale University in 1839. He practiced law in Savannah, and was appointed U.S. district attorney. In an ironic twist of history, Jackson served as colonel of the First Georgia Regiment during the Mexican War. During the years between the Mexican and Civil Wars Jackson held the offices of superior court judge and United States minister to Austria. In 1860, he was a delegate to the Charleston Democratic Convention, and in 1861 attended the Georgia Secession Convention. That year he was received an appointment as a Confederate States court judge, but on July 4 he was commissioned a Confederate brigadier general. Jackson was enroute from Richmond to Monterey with reinforcements for General Garnett’s Army of the Northwest when he learned of Garnett’s disastrous retreat from Laurel Hill. Jackson was ordered to assume command of the Army of the Northwest as the exhausted and demoralized troops straggled into Monterey. When General William W. Loring arrived a few days later to take command of the Northwestern army, Jackson was given a brigade which included Ramsey’s First Georgia. During General Robert E. Lee’s failed Cheat Mountain campaign, Jackson’s brigade demonstrated against the Union fort at Cheat Pass, and was the last Confederate command to be withdrawn. On October 3, Jackson’s troops were attacked at Camp Bartow on the Greenbrier River. Unable to make headway against Jackson’s entrenchments, the Union forces withdrew, giving the Army of the Northwest a much needed victory. Jackson resigned his Confederate commission in December and returned to Georgia to accept a commission from Governor Joseph E. Brown as a state Major General. Left without a command when his state troops were transferred to Confederate service, Jackson was attached to the staff of General W. H. T. Walker, who commanded a division in the Army of Tennessee. In September of 1863, he was reinstated as a Confederate brigadier, and commanded a brigade during the battles of Jonesboro and Franklin. During the Confederate defeat at Nashville (December 15-16, 1864), his brigade was surrounded and captured. Jackson was first sent to Johnson’s Island, Ohio, then was transferred to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. Released in July of 1865, Jackson returned to Georgia and resumed his law practice. He served as United States minister to Mexico from 1885 to 1887, but resigned in a dispute over U.S. policy. He was appointed as a director of the Georgia Central Railroad and Banking, and served as president of the Georgia Historical Society. Henry R. Jackson died in Savannah on May 23, 1898.

---------------------------------------------------

On a personal note, I will be traveling over the next week. On Tuesday night I will be in northern New Hampshire, speaking to the Colebrook Historical Society about my ancestors, William Henry Marshall and Cummings Marshall. Readers of this blog will remember my posts on the two brothers about how they came to serve on opposing sides in the Civil War.

Thursday, August 26, 2010

Gettysburg Casino

The Civil War Preservation Trust has just issued a news release on a new study showing the adverse impact of the proposed Mason-Dixon Casino at Gettysburg.

* * * * * * * * *

INDEPENDENT ANALYSIS REVEALS DEEP FLAWS IN PROPOSED GETTYSBURG CASINO ECONOMIC PROJECTIONS

Examination discloses that casino would have “serious, substantial and sustained adverse impacts” to the Gettysburg Battlefield and surrounding community

(Gettysburg, Pa.) – Today a coalition of preservation groups working with local business owners involved in Businesses Against the Casino released an independent assessment of the potential impacts of gaming on Gettysburg and Adams County. The report, Impacts of the Proposed Mason-Dixon Casino on the Gettysburg Area – A Realistic Assessment, found that the application for a resort casino license near Gettysburg greatly exaggerates the economic impact of the proposal and ignores the “serious, substantial and sustained adverse impacts” it poses for existing businesses and the battlefield.

The report was commissioned by the Civil War Preservation Trust (CWPT), National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), National Trust for Historic Preservation and Preservation Pennsylvania on behalf of the Adams County organization Businesses Against the Casino. Author Michael Siegel of Public and Environmental Finance Associates of Washington, D.C., has more than 30 years experience in public and environmental finance and impact analysis.

“Appropriate scrutiny shows the analysis performed by Mason-Dixon in support of its application to be insufficient and amateurish,” said CWPT president James Lighthizer. “The document mentions no potential impacts on the Borough of Gettysburg — where existing businesses are at ground zero for negative fallout — despite explicit requirements for such consideration in application materials.”

“Gettysburg National Military Park is already an economic engine for the surrounding communities,” said Cinda Waldbuesser, NPCA Pennsylvania senior program manager. “This independent analysis shows that Mason Dixon’s promises of economic gain are exaggerated and ignore the impacts that the casino will have on the park. Licensing a casino so close to the battlefield would put a known economic engine at risk in favor of an unknown venture.”

Based on the many important findings revealed in A Realistic Assessment, Charles McElhose, a local business owner and a spokesman for Businesses Against the Casino, believes it should be required reading for every business owner and local resident.

“Claims made about a project of this scale must be able to withstand close examination,” said McElhose. “Many things were unaccounted for, or perhaps purposefully omitted, in the Mason-Dixon impact report. This new analysis is crucial to obtaining a full understanding of the impacts this casino will have on our community. It stands to affect the bottom line of every local business — especially those serving heritage tourists, but, likewise, the companies that provide products and services to those businesses. There is very real potential for a “snowball effect” that could devastate our economy.”

Key findings of A Realistic Assessment include:

NUMBER AND TYPE OF JOBS MIS-STATED

Casino proponents claim the facility will bring hundreds of good jobs to the community. By comparing apples to oranges, the Local Impact Report confidently announces that the facility will create approximately 900 “net new jobs” for Adams County. That figure, however, is a confused and deceptive jumble of “full-time equivalent,” full- and part-time jobs to which further ancillary positions were also added, based on an inappropriate, misleading, and undocumented statistical multiplier. This causes the LIR’s projection of jobs to be unreliable and overstated.

The LIR’s economic analysis does not mention the actual number of on-site jobs it has assumed to be at the proposed casino, instead citing a figure of 375 full-time equivalent jobs. As A Realistic Assessment documents, this is actually a mix of 1,087 full and part-time jobs. Realizing that the average salary is $17,061 per year — just $.95 above state minimum wage requirements— indicates that the majority of those positions will be part-time jobs rather than full-time or career positions.

ASSUMED STAFFING LEVEL IS GREATER THAN ATLANTIC CITY’S LARGEST, HIGHEST VALUE CASINO

Among the most unreasonable assertions put forward in the Mason-Dixon LIR is that the proposed casino would support more jobs per gaming position — the individual seats for gamblers at a slot machines and table games — than the largest, highest-value destination casino in Atlantic City, N.J. Based on Mason-Dixon’s projections, the casino would employ 1.21 individuals per gaming position (nearly 1,100 jobs for 900 gaming seats). By contrast, Atlantic City’s Borgata Hotel, Casino & Spa, the second largest casino complex in the country, has a ratio of just 1.19 jobs per gaming position, while the average for Atlantic City is .90. Adjusting the projections from the Crossroads Gaming Resort and Spa — proposed for the identical market area in 2005–2006 — to include the same number of table games, it would yield only .55 jobs per seat.

The Applicant claims its facility — serving a primarily local and convenience market — would proportionally have more jobs than Atlantic City’s Borgata resort complex, which dwarfs Mason-Dixon in scale and scope. The estimated construction cost for Mason-Dixon is $27.03 million, while the 2009 value of the Borgata was $1.77 billion.

SACRIFICING EXISTING BUSINESSES FOR A NEW VENTURE

The LIR’s economic analysis is based on the odd proposition that none of Gettysburg’s existing businesses will be hurt when residents and current visitors spend their money at the proposed casino instead of local shops and restaurants. Based on the spending of local residents in other casino communities, area residents would annually gamble away $776 per person, or $68.3 million, at Mason Dixon — plus another nearly $18 million in estimated food, beverage and entertainment spending. Estimating half that sum would otherwise have been spent locally, that’s $43 million annually siphoned out of the pockets of local residents and businesses. Based on Mason-Dixon’s estimates, existing visitors to the community are conservatively estimated to spend an average of about $35 each at the casino, for a total annual diversion of about $78.4 million from existing county businesses, ultimately resulting in the loss of as many as 1,130 existing jobs in the community. Many positions, following the spending that supports them would be transferred to the proposed casino. But the LIR fails to recognize this, as its methodology is incapable of distinguishing between a legitimate net new job and one transferred from a local business.

SKIPPING THE BATTLEFIELD FOR THE SLOTS: VICKSBURG’S POST CASINO EXPERIENCE

The previous application for a casino oriented to the identical market area as Mason-Dixon relied heavily on touting Vicksburg, Miss., as a model of how a casino would affect Gettysburg and the surrounding area — specifically that visitation to Vicksburg National Military Park (NMP) was unaffected and actually benefitted from the introduction of casinos. Vicksburg was once a close, second to Gettysburg, in visitation among National Park Service Civil War sites, but in 1994, the first year all four Vicksburg casinos were open, visitation plunged 20 percent. By 1998, visitation had ultimately recovered to its pre-casino level and remained relatively stable until Hurricane Katrina caused another steep decline in 2005. But the ability for visitation to Vicksburg’s historic battlefield to bounce back seems to be exhausted. Unlike other national parks in Mississippi and Louisiana, which have returned to their pre-hurricane levels, Vicksburg’s visitation remains at levels not seen since the imposition of visitor fees in the 1980s or the 1970’s oil embargo, and the link cannot be ignored or easily dismissed.

Vicksburg’s main casino complex lies about 2.5 miles south of its historic Main Street area, roughly 4 miles from the main entrance to Vicksburg NMP and 1 mile from the park boundary — distances that are comparable to the proposed Gettysburg site. Between 1992 and 1994, when visitation plummeted, traffic bypassing the park’s entrance increased by the same percentage, while traffic on a key access segment of old Highway 61 running directly to the casinos exploded by 64 percent. Today, traffic through downtown Vicksburg is 17 percent lower than it was in 1998. As A Realistic Assessment concludes: “The pattern is clear: traffic to casinos up; traffic and visitation at Vicksburg’s two most significant historical, cultural, and tourism sites down.”

FAILURE TO CONSIDER GEOGRAPHIC COMPETITION

In rejecting the 2006 Crossroads Application, the Gaming Control Board cited the applicant’s failure to adequately address its potential geographic disadvantage, as other neighboring states were contemplating adding or expanding their gambling options. Since then, the regional gaming landscape has changed dramatically. In West Virginia, table games have been added to existing casinos, including nearby Charles Town Races and Slots. Delaware will soon add table games of its own, and the nearby Dauphin County casino overlaps with the market area that Mason-Dixon would draw upon.

Most significantly, however, the LIR fails to note the effect of the soon-to-open Maryland casinos — which were only a possibility at the time of the 2006 application, although their impact was a serious concern to the PGCB. This could cause the proposed casino to lose tens of thousands — if not a hundred thousand or more of its expected visitors following their opening

---------------------------------------------

More information about the CWPT's efforts to block the casino can be found here.

* * * * * * * * *

INDEPENDENT ANALYSIS REVEALS DEEP FLAWS IN PROPOSED GETTYSBURG CASINO ECONOMIC PROJECTIONS

Examination discloses that casino would have “serious, substantial and sustained adverse impacts” to the Gettysburg Battlefield and surrounding community

(Gettysburg, Pa.) – Today a coalition of preservation groups working with local business owners involved in Businesses Against the Casino released an independent assessment of the potential impacts of gaming on Gettysburg and Adams County. The report, Impacts of the Proposed Mason-Dixon Casino on the Gettysburg Area – A Realistic Assessment, found that the application for a resort casino license near Gettysburg greatly exaggerates the economic impact of the proposal and ignores the “serious, substantial and sustained adverse impacts” it poses for existing businesses and the battlefield.

The report was commissioned by the Civil War Preservation Trust (CWPT), National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), National Trust for Historic Preservation and Preservation Pennsylvania on behalf of the Adams County organization Businesses Against the Casino. Author Michael Siegel of Public and Environmental Finance Associates of Washington, D.C., has more than 30 years experience in public and environmental finance and impact analysis.

“Appropriate scrutiny shows the analysis performed by Mason-Dixon in support of its application to be insufficient and amateurish,” said CWPT president James Lighthizer. “The document mentions no potential impacts on the Borough of Gettysburg — where existing businesses are at ground zero for negative fallout — despite explicit requirements for such consideration in application materials.”

“Gettysburg National Military Park is already an economic engine for the surrounding communities,” said Cinda Waldbuesser, NPCA Pennsylvania senior program manager. “This independent analysis shows that Mason Dixon’s promises of economic gain are exaggerated and ignore the impacts that the casino will have on the park. Licensing a casino so close to the battlefield would put a known economic engine at risk in favor of an unknown venture.”

Based on the many important findings revealed in A Realistic Assessment, Charles McElhose, a local business owner and a spokesman for Businesses Against the Casino, believes it should be required reading for every business owner and local resident.

“Claims made about a project of this scale must be able to withstand close examination,” said McElhose. “Many things were unaccounted for, or perhaps purposefully omitted, in the Mason-Dixon impact report. This new analysis is crucial to obtaining a full understanding of the impacts this casino will have on our community. It stands to affect the bottom line of every local business — especially those serving heritage tourists, but, likewise, the companies that provide products and services to those businesses. There is very real potential for a “snowball effect” that could devastate our economy.”

Key findings of A Realistic Assessment include:

NUMBER AND TYPE OF JOBS MIS-STATED

Casino proponents claim the facility will bring hundreds of good jobs to the community. By comparing apples to oranges, the Local Impact Report confidently announces that the facility will create approximately 900 “net new jobs” for Adams County. That figure, however, is a confused and deceptive jumble of “full-time equivalent,” full- and part-time jobs to which further ancillary positions were also added, based on an inappropriate, misleading, and undocumented statistical multiplier. This causes the LIR’s projection of jobs to be unreliable and overstated.

The LIR’s economic analysis does not mention the actual number of on-site jobs it has assumed to be at the proposed casino, instead citing a figure of 375 full-time equivalent jobs. As A Realistic Assessment documents, this is actually a mix of 1,087 full and part-time jobs. Realizing that the average salary is $17,061 per year — just $.95 above state minimum wage requirements— indicates that the majority of those positions will be part-time jobs rather than full-time or career positions.

ASSUMED STAFFING LEVEL IS GREATER THAN ATLANTIC CITY’S LARGEST, HIGHEST VALUE CASINO

Among the most unreasonable assertions put forward in the Mason-Dixon LIR is that the proposed casino would support more jobs per gaming position — the individual seats for gamblers at a slot machines and table games — than the largest, highest-value destination casino in Atlantic City, N.J. Based on Mason-Dixon’s projections, the casino would employ 1.21 individuals per gaming position (nearly 1,100 jobs for 900 gaming seats). By contrast, Atlantic City’s Borgata Hotel, Casino & Spa, the second largest casino complex in the country, has a ratio of just 1.19 jobs per gaming position, while the average for Atlantic City is .90. Adjusting the projections from the Crossroads Gaming Resort and Spa — proposed for the identical market area in 2005–2006 — to include the same number of table games, it would yield only .55 jobs per seat.

The Applicant claims its facility — serving a primarily local and convenience market — would proportionally have more jobs than Atlantic City’s Borgata resort complex, which dwarfs Mason-Dixon in scale and scope. The estimated construction cost for Mason-Dixon is $27.03 million, while the 2009 value of the Borgata was $1.77 billion.

SACRIFICING EXISTING BUSINESSES FOR A NEW VENTURE

The LIR’s economic analysis is based on the odd proposition that none of Gettysburg’s existing businesses will be hurt when residents and current visitors spend their money at the proposed casino instead of local shops and restaurants. Based on the spending of local residents in other casino communities, area residents would annually gamble away $776 per person, or $68.3 million, at Mason Dixon — plus another nearly $18 million in estimated food, beverage and entertainment spending. Estimating half that sum would otherwise have been spent locally, that’s $43 million annually siphoned out of the pockets of local residents and businesses. Based on Mason-Dixon’s estimates, existing visitors to the community are conservatively estimated to spend an average of about $35 each at the casino, for a total annual diversion of about $78.4 million from existing county businesses, ultimately resulting in the loss of as many as 1,130 existing jobs in the community. Many positions, following the spending that supports them would be transferred to the proposed casino. But the LIR fails to recognize this, as its methodology is incapable of distinguishing between a legitimate net new job and one transferred from a local business.

SKIPPING THE BATTLEFIELD FOR THE SLOTS: VICKSBURG’S POST CASINO EXPERIENCE

The previous application for a casino oriented to the identical market area as Mason-Dixon relied heavily on touting Vicksburg, Miss., as a model of how a casino would affect Gettysburg and the surrounding area — specifically that visitation to Vicksburg National Military Park (NMP) was unaffected and actually benefitted from the introduction of casinos. Vicksburg was once a close, second to Gettysburg, in visitation among National Park Service Civil War sites, but in 1994, the first year all four Vicksburg casinos were open, visitation plunged 20 percent. By 1998, visitation had ultimately recovered to its pre-casino level and remained relatively stable until Hurricane Katrina caused another steep decline in 2005. But the ability for visitation to Vicksburg’s historic battlefield to bounce back seems to be exhausted. Unlike other national parks in Mississippi and Louisiana, which have returned to their pre-hurricane levels, Vicksburg’s visitation remains at levels not seen since the imposition of visitor fees in the 1980s or the 1970’s oil embargo, and the link cannot be ignored or easily dismissed.

Vicksburg’s main casino complex lies about 2.5 miles south of its historic Main Street area, roughly 4 miles from the main entrance to Vicksburg NMP and 1 mile from the park boundary — distances that are comparable to the proposed Gettysburg site. Between 1992 and 1994, when visitation plummeted, traffic bypassing the park’s entrance increased by the same percentage, while traffic on a key access segment of old Highway 61 running directly to the casinos exploded by 64 percent. Today, traffic through downtown Vicksburg is 17 percent lower than it was in 1998. As A Realistic Assessment concludes: “The pattern is clear: traffic to casinos up; traffic and visitation at Vicksburg’s two most significant historical, cultural, and tourism sites down.”

FAILURE TO CONSIDER GEOGRAPHIC COMPETITION

In rejecting the 2006 Crossroads Application, the Gaming Control Board cited the applicant’s failure to adequately address its potential geographic disadvantage, as other neighboring states were contemplating adding or expanding their gambling options. Since then, the regional gaming landscape has changed dramatically. In West Virginia, table games have been added to existing casinos, including nearby Charles Town Races and Slots. Delaware will soon add table games of its own, and the nearby Dauphin County casino overlaps with the market area that Mason-Dixon would draw upon.

Most significantly, however, the LIR fails to note the effect of the soon-to-open Maryland casinos — which were only a possibility at the time of the 2006 application, although their impact was a serious concern to the PGCB. This could cause the proposed casino to lose tens of thousands — if not a hundred thousand or more of its expected visitors following their opening

---------------------------------------------

More information about the CWPT's efforts to block the casino can be found here.

Saturday, August 21, 2010

Flags of the First Georgia

When the various companies which would make up the First Georgia Infantry arrived in Macon, each one bore with them beautiful flags. As in communities across the South, these banners were most often sewn by groups of local ladies and presented to the troops in elaborate ceremonies. Many (if not most) of these flags were of a pattern mimicking the new national colors, known as the “Stars and Bars”. Today also known as the First National Flag of the Confederacy, the banner contained of a blue canton containing a pattern of stars, and the field consisted of three horizontal wide stripes (“bars”) of two red and one white.*

The first company to arrive at Macon’s Camp Oglethorpe in early April, 1861, was the Quitman Guards of Monroe County. The Guards’ flag, patterned after the First National, was described in an 1883 newspaper article about a regimental reunion of First Georgia veterans:

“The old flag of the Quitman Guards attracted a great deal of attention. It has many a ghastly gash where the vicious bullets split their way through its fleecy folds, but it is yet in a fair state of preservation, and though the white silk fringe with which fair hands decked its borders is stained and torn, its red, white and blue bars and golden stars stirs the memories of the heart and calls up again the dark days of ’61, when the pride of many a home and the idol of many a heart marched away so proudly away, never, alas, to return again, with it waving so gaily above them. I am as strong for fraternization as anybody, but if I am to do so at the expense of the memory of the men who fell under that flag I will have none of it. Thank heaven there are no longer any to say that the men who marched and fought under the stars and bars were not as noble, as brave, and as honest in their convictions as those who fought under the stars and stripes.”

The major difference between the Quitman Guards’ flag and most First National pattern banners is in the canton. Where in most flags the canton meets the seam of the lowest bar, covering the field of the top two bars, in the Guard’s banner the canton comes down just to the top seam of the middle, white bar. This is my rendering of this flag:

The Monroe County Historical Society holds a photograph of Monroe County veterans, a portion of which is at left. In the right background is displayed a First National Flag. During my research I was advised that this was probably the flag of the Fourteenth Georgia, which is now in the collection of the Georgia Capitol Museum in Atlanta, and can be seen here. Confederate flag authority Greg Biggs, who was of great help with I Will Give Them One More Shot, has studied the photo, and agrees that it is most likely the flag of the Quitman Guards. The flag in the photograph quite plainly displays a fringe, and though shows the obverse, there is no shadow or bleed through of lettering from the front side. The flag of the Fourteenth Georgia has the regiment’s name stenciled on the length of the white bar. Also, the canton of the Fourteenth’s flag projects slightly down into the white bar, while the canton of the flag in the veteran’s photograph appears to run even with the top and middle bars’ seams. Lastly, the Fourteenth’s flag shows no evidence of having had a fringe. It is quite possible that both flags were made by the same person or persons.

-----------------------------------------

*A pet peeve of mine is today’s common habit of calling any Confederate flag the Stars and Bars – most frequently confusing it with the Battle Flag (or Southern Cross) with its St. Andrew’s cross.

The first company to arrive at Macon’s Camp Oglethorpe in early April, 1861, was the Quitman Guards of Monroe County. The Guards’ flag, patterned after the First National, was described in an 1883 newspaper article about a regimental reunion of First Georgia veterans:

“The old flag of the Quitman Guards attracted a great deal of attention. It has many a ghastly gash where the vicious bullets split their way through its fleecy folds, but it is yet in a fair state of preservation, and though the white silk fringe with which fair hands decked its borders is stained and torn, its red, white and blue bars and golden stars stirs the memories of the heart and calls up again the dark days of ’61, when the pride of many a home and the idol of many a heart marched away so proudly away, never, alas, to return again, with it waving so gaily above them. I am as strong for fraternization as anybody, but if I am to do so at the expense of the memory of the men who fell under that flag I will have none of it. Thank heaven there are no longer any to say that the men who marched and fought under the stars and bars were not as noble, as brave, and as honest in their convictions as those who fought under the stars and stripes.”

The major difference between the Quitman Guards’ flag and most First National pattern banners is in the canton. Where in most flags the canton meets the seam of the lowest bar, covering the field of the top two bars, in the Guard’s banner the canton comes down just to the top seam of the middle, white bar. This is my rendering of this flag:

-----------------------------------------

*A pet peeve of mine is today’s common habit of calling any Confederate flag the Stars and Bars – most frequently confusing it with the Battle Flag (or Southern Cross) with its St. Andrew’s cross.

Thursday, August 12, 2010

William Booth Taliaferro

When the First Georgia marched into the works at Laurel Hill, Colonel William B. Taliaferro (pronounced TOL-li-ver) of the Twenty-Third Virginia was more impressed with their uniforms than with their martial bearing. Born December 28, 1822, Taliaferro was educated at Harvard University and William and Mary, and served in the Eleventh and Ninth U.S. Infantry during the Mexican War. He was a member of the Virginia legislature from 1850 to 1853. After John Brown’s raid in 1859, Taliaferro was assigned as commander of Virginia militia at Harper’s Ferry, and following Virginia’s secession was promoted to major-general of the state’s militia. Appointed as colonel of the Twenty-Third Virginia Infantry in May of 1861, Taliaferro was assigned to General Garnett’s Army of the Northwest. Friction quickly developed between Taliaferro and the Georgians, partially due to the fact that, even though Ramsey’s military experience was miniscule compared to Taliaferro’s, Ramsey’s commission predated the Virginian’s. After General Garnett was killed at Corricks Ford, Ramsey was ill and unable to take charge, so Colonel Taliaferro directed the army’s retreat until Colonel Ramsey recovered enough to assume command.

During the Battle of Greenbrier River, Taliaferro commanded General Henry R. Jackson’s center, and upon Jackson’s departure from the army, Taliaferro was given his brigade. Friction continued between Taliaferro and the Georgians – at one point the colonel was assaulted by a drunken Georgia soldier.

Late in 1861, Taliaferro’s brigade, along with two others from the Army of the Northwest, were ordered to Winchester to join General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson command. On January 1, 1862, Jackson embarked on his Romney Campaign, during which his soldiers suffered greatly during prolonged marches in snow and ice. After Romney was occupied on January 14, Jackson decided to leave the three brigades of the Army of the Northwest to garrison the town, and returned with his “Stonewall” Brigade to Winchester. This led to hard feelings among the officers and men of the Northwestern army.

Fed up with the squalid conditions in Romney, most of the officers of the Army of the Northwest signed the infamous “Romney Petition,” which declared that the town was exposed and indefensible, and to implore the leadership to order the army’s removal. Obtaining leave, Taliaferro traveled to Richmond to plead the army’s case directly to Jefferson Davis, Alexander Stephens and Judah P. Benjamin. The Petition, Taliaferro’s politicking and other factors convinced Davis that Romney should be evacuated, so he instructed Benjamin to order Jackson to withdraw the troops to Winchester. Jackson did so, but incensed over having his authority overridden, submitted his resignation. (He was persuaded later to relent) The ill will between Jackson and Army of the Northwest commander General William W. Loring led the authorities in Richmond to break up the Northwestern army, sending some units west, and added all the Virginia units, including Taliaferro’s troops, to Jackson’s Valley Army.

Promoted to Brigadier General in March of 1862, Taliaferro continued to command a brigade under Jackson, and was wounded at the Battle of Second Manassas. After a period of convalescence, he returned to army prior to the Battle of Fredericksburg. Following that campaign, Taliaferro was transferred to District of Savannah, then later Eastern Florida. He led a division at the Battle of Bentonville, and finished the war in command of South Carolina forces.

Returning home, Taliaferro was appointed to a judgeship, and reentered politics as a member of the Virginia legislature. He also served on the boards of visitors of the College of William and Mary and VMI. Taliaferro died on February 27, 1898, and is buried in Gloucester County, Virginia.

Sunday, August 1, 2010

General Robert S. Garnett

Devastated when his wife and only child died of disease in 1858, Garnett took an extended leave of absence and traveled to Europe. He returned home one month before Virginia’s secession, at which time he resigned his commission in the U.S. Army. Shortly thereafter he was commissioned as Colonel and appointed adjutant general of Virginia. After the humiliating Confederate defeat at Phillippi on June 3, 1861, Garnett was promoted to brigadier general and given command of the forces in Western Virginia, from which the Army of the Northwest was created. Garnett’s forces entrenched at Laurel Hill and Rich Mountain to guard vital roadways passing through the Allegheny Mountains. Following the defeat of his troops at Rich Mountain on July 11, Garnett retreated from Laurel Hill, first south toward his depot at Beverly, then north toward Maryland. Skirmishes between his troops and pursuing Union forces occurred at Kalers Ford and the two river crossings of Corricks Ford. At the second Corricks Ford crossing, Garnett was killed by Union fire, earning the dubious honor of being the first general officer on either side to be killed in the Civil War. His body was recovered by Federal troops, and was taken by family members to Baltimore. Following the end of the war, Garnett’s remains were reinterred next to his wife and child in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. His monument makes no mention of his military service, but a veteran’s stone placed later says “Brig Gen Robert S. Garnett CSA 1819 1861.”

Friday, July 23, 2010

The Commanders

During its one year of existence, the First Georgia served under several commanders, some relatively unknown, others already famous or soon to become so. Over the next few posts, I will introduce the officers who commanded Colonel Ramsey’s Georgians.

After the First was organized at Macon in April, 1861, the regiment was ordered to Pensacola to join the forces commanded by Brigadier General Braxton Bragg. Born in North Carolina in 1817, Bragg attended West Point, graduating fifth in the class of 1837. He was commissioned a second lieutenant with the U.S. Third Artillery, and saw service against the Seminole Indians in Florida. During the War with Mexico, Bragg served with the U.S. Fifth Artillery under General Zachary Taylor. During a Mexican attack during the Battle of Buena Vista, Taylor reportedly ordered Bragg to “give ‘em a little more grape.” The phrase stuck, and was associated with Bragg for years. At the outset of the Civil War, Bragg rose quickly from militia colonel to a Confederate brigadier general, his rise helped by his friendship with President Jefferson Davis. An uneven career as commander of different Confederate armies and conflicts with subordinates have caused much controversy about his military legacy. The general ended the war as President Davis’s military advisor. He later held positions as Chief Engineer for the State of Alabama and as a railroad inspector in Texas. Bragg died on September 27, 1876, in Galveston, and was buried in Mobile, Alabama.

Braxton Bragg

After the First was organized at Macon in April, 1861, the regiment was ordered to Pensacola to join the forces commanded by Brigadier General Braxton Bragg. Born in North Carolina in 1817, Bragg attended West Point, graduating fifth in the class of 1837. He was commissioned a second lieutenant with the U.S. Third Artillery, and saw service against the Seminole Indians in Florida. During the War with Mexico, Bragg served with the U.S. Fifth Artillery under General Zachary Taylor. During a Mexican attack during the Battle of Buena Vista, Taylor reportedly ordered Bragg to “give ‘em a little more grape.” The phrase stuck, and was associated with Bragg for years. At the outset of the Civil War, Bragg rose quickly from militia colonel to a Confederate brigadier general, his rise helped by his friendship with President Jefferson Davis. An uneven career as commander of different Confederate armies and conflicts with subordinates have caused much controversy about his military legacy. The general ended the war as President Davis’s military advisor. He later held positions as Chief Engineer for the State of Alabama and as a railroad inspector in Texas. Bragg died on September 27, 1876, in Galveston, and was buried in Mobile, Alabama.

Henry D. Clayton

After their arrival in Pensacola, the Georgians were assigned to Bragg’s Second Brigade, under the command of Colonel Henry D. Clayton. Born in Pulaski County, Georgia, on March 7, 1827, Clayton moved to Eufaula, Alabama after graduating from Emory and Henry College in Virginia. In August 1860, he was elected colonel of the 3rd Volunteers, an Alabama militia unit. Sent to Pensacola in early 1861, the Volunteers were mustered into Confederate service as the 1st Alabama Infantry. General Bragg gave the colonel command of the Second Brigade, which contained his regiment and the Second Alabama Battalion. Clayton resigned his commission in January 1862 and raised a new regiment, the 39th Alabama, which saw service Perryville and Stones River, where he was wounded. He was promoted to brigadier general on 1863, and served with the Army of Tennessee through its many battles. Clayton was promoted to Major General in 1864, commanding a division at the Battles of Franklin and Nashville. Worn out with the stress of command, Clayton resigned from the army shortly before its surrender in April of 1865. After war’s end, Clayton served as a circuit court judge and as president of the University of Alabama. He died in 1889.

Monday, July 19, 2010

Book Work Continues

My apologies for the lack of posts over the past few weeks. Several family emergencies and a week and a half of intense copyedit work on I Will Give Them One More Shot have kept me preoccupied. More posts to come soon.

Thursday, June 24, 2010

Flags of Bentonville