Once the disaster of Garnett’s defeats in Western Virginia became known, Richmond dispatched a new commander to take charge of the demoralized Army of the Northwest. When Brigadier General William Wing Loring arrived in Staunton, he was stunned to find soldiers from the First Georgia Regiment scattered across the countryside. Livid at what he considered a serious breach of discipline, Loring promptly had Colonel Ramsey placed under arrest.

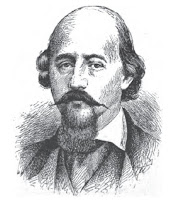

William Wing Loring was born in Wilmington, North Carolina, on December 4, 1818. At the age of four his parents moved to St. Augustine, Florida. Loring began his military career at the tender age of fourteen, joining the Florida militia to fight against the Seminole Indians, eventually achieving the rank of second lieutenant. Sent by his parents to Virginia to complete his education, Loring graduated from Georgetown University in 1840. Returning to Florida, he practiced law and was elected to the Florida legislature.

In 1846, Loring was appointed as captain in the Regiment of Mounted Rifles, and was quickly promoted to major. The Regiment saw action during the Mexican War. While leading a charge at Chapultepec, Loring was hit in his left arm, and the shattered limb was amputated. For his meritorious service, Loring was brevetted to Lt. Colonel and Colonel. After the war, Loring was posted to the Oregon territory, and later served at various western outposts.

In late 1856 he was promoted to colonel, giving him the distinction of being the youngest full colonel in field command in the U.S. Army. Loring took a leave of absence in 1859 to tour Europe and the Middle East. Upon his return to the United States, he was given command of the Department of New Mexico.

With the secession of Florida, Loring sided with the Southern cause, resigning his commission in May of 1861. Traveling to Richmond, he was given a commission as brigadier general. Following the death of General Robert S. Garnett, Loring was ordered to take command of the Army of the Northwest. Loring was less than enthusiastic when shortly thereafter General Robert E. Lee arrived to take charge, as Loring had ranked Lee in the old army, and still considered him a subordinate. When in December 1861, Loring and three of his brigades were attached to the forces of General Thomas J. Jackson at Winchester, Loring found himself constantly at odds with the secretive “Stonewall.” The simmering feud finally led to Jackson preferring charges against Loring. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin decided it was time to separate the warring generals. The Army of the Northwest was broken up, and Loring was promoted to major general and given command of the Department of Norfolk, then later the Department of Southwestern Virginia. In January of 1863 he was ordered to the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana, where he commanded a division in the army of General Joseph Pemberton. In an engagement against Union gunboats, Loring shouted to his men to “give them blizzards!” He was known as “Old Blizzards” from then on. During the Vicksburg Campaign, his division was cut off from Pemberton’s force at Champion Hill. Loring marched his troops to join forces with General Joseph E. Johnston’s, where his division was attached to the corps of General Leonidas Polk. During the Atlanta Campaign, Loring was wounded at the Battle of Ezra Church. Loring remained with the Army of Tennessee through Hood’s Tennessee and Johnston’s Carolinas Campaigns, surrendering with that army at Durham Station, North Carolina, on April 26, 1865.

Following the end of the war, Loring tried his hand at banking in New York City, then in December 1869, he accepted a commission in the Egyptian Army. He spent ten years in Egypt, ultimately earning the rank of “Fareek Pasha” (major-general). Returning to the Florida, Loring ran unsuccessfully for U.S. senator, after which he moved back to New York City. He died there on December 30, 1886, and his remains were returned to St. Augustine, Florida, and interred in Woodlawn Cemetery.

.jpg)